Ancestry and studies at the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum

|

| 1. |

|

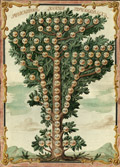

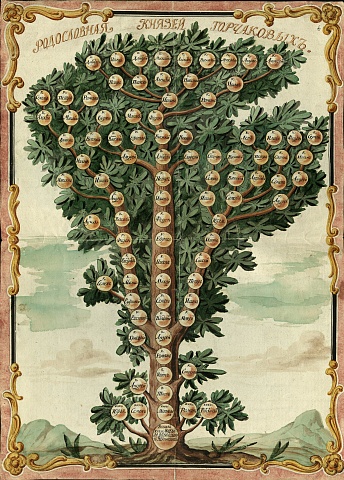

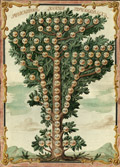

Genealogical tree of the Gorchakov princely family

Undated

|

| 2. |

|

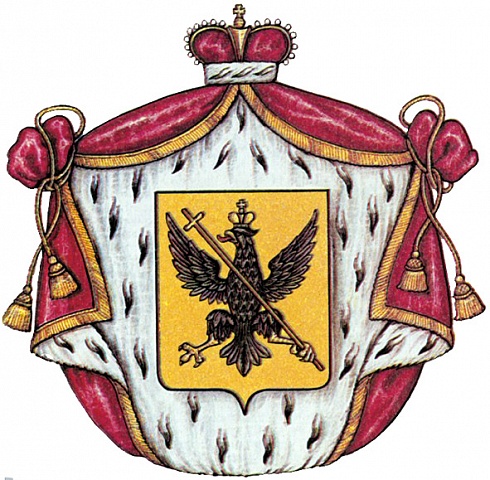

Coat of arms of the Gorchakov princely family

|

| 3. |

|

Portrait of Alexander Gorchakov

1811 or later

This is Alexander Gorchakov’s first portrait, painted in the 1810s when he was studying at the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. While the author is unknown, it may have been painted by the school’s arts teacher, Sergey Chirikov, who painted quite a few of his students at the lyceum. Alexander Gorchakov appears in the portrait wearing his school uniform.

|

| 4. |

|

Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum

1822

Etching by J. Moyer

The Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum was an elite educational institution founded in 1810 by Emperor Alexander I and opened in October 1811. Its fame comes from its class of 1817, which included Alexander Gorchakov, Alexander Pushkin, Anton Delvig, Wilhelm Küchelbecker, and Ivan Pushchin among its graduates. The lyceum trained many prominent diplomats, and some of them went on to serve as the country’s foreign ministers, including Nikolay Girs, Alexey Lobanov-Rostovsky, Nikolay Shishkin, Alexander Izvolsky, and Sergey Sazonov.

|

| 5. |

.jpg)

|

Report by Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum supervisor for educational and moral excellence Vasily Chachkov titled Personal Traits and Behaviour of Imperial Lyceum’s Students

September 30, 1813

“5. Prince Alexander Gorchakov is intelligent, noble in his deeds, devoted to his studies, as well as tidy, polite, studious, sensitive, and modest. He stands out by his amour-propre, and focus on being useful and honourable, as well as his generosity.

24. Alexander Pushkin is light-minded, frivolous, untidy, and careless; at the same time, he has a good heart, dedication, respect, and a knack for poetry.”

|

| 6. |

.jpg)

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s letter to his uncle and guardian Alexey Peshchurov about choosing a diplomatic career

April 22, 1816

“… I decided to enter public service, and among the possible options, following your advice, chose diplomacy as the most noble of them all.”

|

| 7. |

|

Alexader Gorchakov’s Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum graduation diploma

June 9, 1817

“Enrolled at the Imperial Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum for six years, Prince Alexander Gorchakov studied the following subjects at this institution: scripture and divine history, logic and moral philosophy, Latin, Russian, German and French languages, universal and Russian history, geography and statistics, natural private and public law, state economy and finance, Russian civil and criminal law, physics, and abstract and applied mathematics, and demonstrated excellent results in these studies and exceptional morality.”

|

| 8. |

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s portrait on the margins of Alexander Pushkin’s manuscript

Early on, Pushkin predicted that Alexander Gorchakov would make a swift and successful career, while anticipating a life full of drama and challenges for himself.

|

|

Joining the Foreign Ministry. Diplomatic service in 1817-1855

|

| 9. |

|

Signed acknowledgment by Collegium of Foreign Affairs officials, including Alexander Gorchakov, Alexander Pushkin and Wilhelm Küchelbecker, stating that they have read and understood the Order issued by Catherine II on August 4, 1791, on the non-disclosure by foreign service officials of classified information and preventing them from visiting foreign representatives at their homes outside of their official duties.

1817

|

| 10. |

|

The oath of First Secretary of the Russian Embassy to Great Britain Alexander Gorchakov in connection with receiving the civil service class rank of a Court Councillor

February 22 /March 6, 1825

|

| 11. |

.jpg)

|

First report by Russia’s Chargé d’Affaires in Tuscany and Lucca Alexander Gorchakov to Vice-Chancellor Karl Nesselrode on the presentation of the letters of credence

April 4/16, 1829

|

| 12. |

|

Portrait of His Serene Highness Alexander Gorchakov

1836

By Moritz Michael Daffinger

|

| 13. |

.jpg)

|

Note by Counsellor of the Russian Embassy in Austria Alexander Gorchakov on his country of stay

1838

The note offers a detailed review of the country’s state officials and describes the situation in Austria.

Appointed Counsellor of the Russian Embassy in Austria in 1833, Alexander Gorchakov was in charge of the embassy during Ambassador Dmitry Tatishchev’s recurring absences.

|

| 14. |

.jpg)

|

Report by Russia’s Ambassador to Württemberg Alexander Gorchakov to Vice-Chancellor Karl Nesselrode on the Kingdom’s domestic and foreign policy

December 26, 1844/January 7, 1845

|

| 15. |

|

Portrait of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolayevna (from Alexander Gorchakov’s collection)

1848

By Nicaise de Keyser

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolayevna (1822-1892) was Emperor Nicholas I’s second daughter. In 1846, she married Crown Prince Karl Friedrich Alexander of Württemberg, who went on to become King Charles I in 1864. Alexander Gorchakov played an active role in concluding this union and signing an agreement to this effect. He maintained warm relations with the Great Duchess for many years afterwards.

Alexander Gorchakov’s appointments to diplomatic posts across Europe enabled him to start a collection of paintings, which he continued expanding for many years.

|

| 16. |

.jpg)

|

Emperor Nicholas I’s letter of credence to the German Confederation on Alexander Gorchakov’s appointment as Russia’s Ambassador

January 28, 1850

|

| 17. |

.jpg)

|

An encrypted telegram by Russia’s Ambassador to Austria Alexander Gorchakov to Chancellor Nesselrode on Austrian Minister-President Count Karl Ferdinand von Buol’s intention to launch a general mobilisation in the German Confederation and support France with its demands on imposing restrictions on Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

January 14/26, 1855

Note on the document added by Emperor Alexander II:

“This provides evidence, if anyone needed it, of what was in stock for us had we let these rascals get what they wanted.”

|

| 18. |

.jpg)

|

Minutes of the Fifth Meeting at the Vienna Conference specifying peace terms following the Crimean War

March 23, 1855

Alexander Gorchakov and Vladimir Titov represented Russia.

The 1855 Vienna Conference brought together diplomats from Russia, Austria, Great Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire. Held during the 1853-1856 Crimean War, it sought to work our peace terms.

|

| 19. |

.jpg)

|

Emperor Alexander II rescript to Russia’s Ambassador to Austria Alexander Gorchakov awarding him the Order of St Alexander Nevsky

July 1, 1855

“For his dedicated and useful service and special endeavours during his mission to Vienna during the talks there, the recipient is hereby most graciously awarded the title of Companion of the Order of St Alexander Nevsky.”

|

|

1856 and Alexander Gorchakov’s appointment as Foreign Minister

|

| 20. |

|

Peace Treaty between Russia, Austria, France, Great Britain, Prussia, as well as the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire

March 30, 1856, Paris

The Treaty signalled the end of the 1853-1856 Crimean War. Under its terms, Russia ceded Kars to the Ottoman Empire in exchange for Sevastopol and other cities in Crimea occupied by those who sided with the Ottoman Empire. Russia also gave up the mouth of the Danube and part of Bessarabia to Moldavia. The Treaty also provided for the freedom of navigation along the Danube under the control of two international commissions, and reaffirmed self-government for Danubian principalities and the Principality of Serbia within the Ottoman Empire. Russia lost the right to patronise the Danubian principalities. But it was the proclamation of the neutral status for the Black Sea in the Treaty’s Article 11 that became the heaviest blow for Russia, since it banned both Russia and the Ottoman Empire from sailing their warships and having their arsenals there.

|

|

21.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander II rescript appointing Alexander Gorchakov Foreign Minister

April 15, 1856

|

|

22.

|

.jpg) |

Alexander Gorchakov’s circular dispatch to Russia’s diplomatic missions abroad on his appointment as foreign minister

April 16, 1856

In the dispatch, Alexander Gorchakov called on the Russian diplomats to face the new reality in the wake of the Paris Treaty by closing their ranks.

Emperor Alexander II left a note on the margins: “Then so be it.”

|

|

23.

|

.jpg) |

Alexander Gorchakov’s circular dispatch to Russia’s diplomatic missions abroad

August 21, 1856

The purpose of this circular letter was to inform the governments of the countries where the Russian diplomats were accredited about the basic tenets of Russia’s foreign policy in the wake of the Crimean War and the 1856 Paris Treaty. Its key objective was to bring about lasting and durable peace while countering efforts to isolate Russia in international affairs.

“Countries which formed a coalition against us chose to respect the rights and independence of governments as their guiding principle. It is not our intention to explore the historical aspect of the matter dealing with the extent to which Russia’s actions allegedly threatened any of these principles. Instead of starting a fruitless debate, our intention consists of applying the very principles proclaimed by the European powers who became our adversaries, either directly or indirectly, and to readily recall them, especially considering that we have been upholding them at all times… It is the Emperor’s desire to live in perfect union with all governments.” In the meantime, the fact that these very powers fail to comply with these principles offers the Russian Emperor grounds and an opportunity to focus on domestic affairs for the wellbeing of his subjects. “Russia stands accused of becoming isolated and remaining silent in the face of facts which run counter to the law and justice. Russia has grown bitter, they say. Russia has not grown bitter. Russia is focusing itself.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the margins: “Then so be it.”

|

|

24.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander II’s certificate awarding Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov the Order of St Vladimir, 1 class

April 17, 1857

“Your actions following the 1855 Vienna Conferences prompted us to appoint you Foreign Minister. You took over this office at a crucial moment after the signing of the Paris Treaty when its terms had to be carried out. This required constant vigilance and caution on your behalf. Any incident in this connection could have cast a shadow over the European political horizon just when it began to clear up. However, guided by your experience and the sincere aspiration to do even more to secure our tranquillity, you managed to avert any negative consequences arising from these misapprehensions and establish Russia’s friendly relations with all powers.”

|

|

25.

|

|

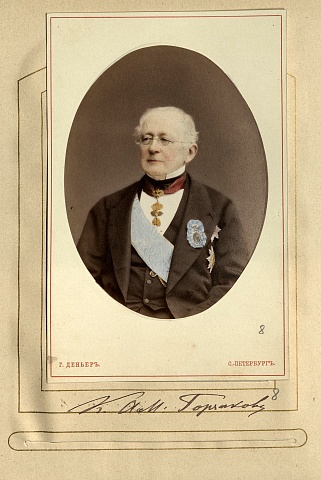

Photographs of Alexander Gorchakov

1860s

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s foreign policy service in 1856-1859

|

|

27.

|

.jpg) |

Instructions by Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov to Russia’s Ambassador to Brazil Konstantin Glinka on the tenets of Russia’s policy regarding this and other Latin American countries

July 11, 1856

“Our relations with this country have always been filled with friendship and mutual sympathy… This large region may well be destined to join the general political mainstream by adding new elements, forces and interests.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

|

|

28.

|

.jpg) |

Most Faithful Report by Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov to Emperor Alexander II on the ratification of the January 26/February 7, 1855 Treaty between Russia and Japan

March 12, 1857

Alexander Gorchakov reported on the exchange of the instruments of ratification and suggested publishing the treaty.

Emperor Alexander II’s note: “To be executed.”

The 1855 Treaty of Shimoda was the first treaty between Russia and Japan on commerce and borders. It proclaimed “permanent peace and sincere friendship” between the two countries.

|

|

29.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov’s instructions to Russia’s Ambassador to Persia Nikolay Anichkov on the basic principles of Russia’s policy in Central Asia

April 12, 1858

“Russia cannot remain indifferent to the situation in which Central Asia finds itself. It seeks to preserve the status quo or prevent it from being upended to the benefit of the British influence.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

|

|

30.

|

.jpg) |

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Russia and China

June 1/13, 1858, Tientsin

The Tientsin Treaty reaffirmed the friendly relations between the two countries and guaranteed personal safety for Chinese and Russian subjects. It also enabled ad interim Russian envoys to be stationed in Beijing and to appoint Russian consuls to the ports that were opened to Russia. Russian traders also secured some preferences. A separate article provided for delineating the Russian-Chinese border in general, even if quite abstract, terms.

|

|

31.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander II’s rescript to Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov awarding him the Order of St Andrew the Apostle the First-Called

August 30, 1858

“With your appointment as foreign minister, we trusted you to guide our policy in keeping with our instructions for the general benefit. Russia’s strengthened friendly relations with the European powers following the signing of the peace treaty earned you our recognition. You have now delivered new major achievements as proven by the Aigun and Tientsin treaties. They put an end to the long-standing border incidents with China, breaking new ground for promoting friendly relations and commerce between our two countries.”

|

|

32.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov’s letters to Emperor Napoleon III of France on the draft of a secret treaty on the Russian-French Union

November 13, 1858

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

In 1856-1859, France turned to Russia seeking its support in a conflict with Austria over territories in Northern Italy. Russia, in turn, wanted France to help it resolve the Oriental Question. The two countries made proactive steps towards one another in the second half of 1858, including with the signing of a secret treaty on neutrality and cooperation on February 19/March 3, 1859.

|

|

33.

|

.jpg) |

Treaty between Russia and Great Britain on Commerce and Navigation

December 31, 1858/January 12, 1859, St Petersburg

Signed by Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov and Ambassador of Great Britain to Russia Sir John Crampton

|

|

34.

|

|

Photograph of Alexander Gorchakov

Undated

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s foreign policy activities in 1862-1870

|

|

35.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov’s letter to the Russian Ambassador to the United States Eduard de Stoeckl on Russia’s position regarding the Civil War in the United States

February 24, 1862

“There is no North or South for us; there is only the federal union. We regret to witness it facing this calamity, and would be disheartened by its disintegration. We stand for temperance and reconciliation and recognise only one government in the United States: the one headquartered in Washington.”

|

|

36.

|

.jpg) |

Edition No. 202 of the Journal de Saint-Pétersbourg with dispatches by Vice-Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov to Russian ambassadors to Great Britain, France and Austria on terminating talks with European countries on the Polish issue

September 9-10/21-22, 1863

In 1863-1864, an uprising broke out in the Kingdom of Poland aimed at restoring the Polish state within the 1772 borders pre-dating the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Guided by their vested interests, Western powers turned to St Petersburg with a collective proposal to convene a conference for settling the Polish crisis. However, Alexander Gorchakov turned down the Western initiative by arguing that the Polish issue was Russia’s internal affair.

|

|

37.

|

.jpg) |

Vice-Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s report to Emperor Alexander II on Russia’s relations with foreign countries after the 1863 uprising in Poland

September 3, 1865

“Considering the current state of our country and Europe in general, Russia must focus primarily on promoting its development internally, while its foreign policy must serve this cause.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note: “Très bien” (“Very well”).

|

|

38.

|

.jpg) |

Vice-Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s letter to Russia Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Nikolay Ignatyev on the resolutions of the Paris Conference regarding the Danubian principalities

July 10, 1866

“…We can well benefit from the violations of the Paris Treaty in order to be able to declare it null and void… The time to act has not yet come…. We must exercise extreme caution in our relations with Christians in the East. Our sympathy for them must never be questioned, as well as the fact that we will never refuse the trust they place in us. However, we must do everything to avoid anything that may encourage aspirations we believe to be premature.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

Convened in March 1866, the Paris Conference brought together Russia, France, Great Britain, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Ottoman Empire, Austria and Prussia to discuss Moldavia and Wallachia and elect its new prince.

The participants recognised the legitimacy of electing a foreign prince to the Romanian throne. From a formal perspective, this constituted a breach of the 1856 Paris Treaty and the resolutions of the 1858 Paris Conference, which provided for the separation of the two principalities. This offered Russia a pretext to start an unofficial probe through its foreign ambassadors in order to gauge the attitude of European powers and the Ottoman Empire towards revising certain provisions of the Paris Treaty dealing with the Black Sea’s neutral status.

|

|

39.

|

|

Foreign Minister of Prussia Otto von Bismarck’s letter to Vice-Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov

November 10, 1866

“Since the early days in my political career, I have never questioned the reliable amity which has existed between our two countries and their rulers for more than a century now. Feelings of personal gratitude and attachment further strengthened my faith in this friendship and my commitment to making it even stronger since my stay in Petersburg. This is why your guarantee regarding my aspirations and our shared interest expressed by your Ein Mann, ein Wort [An honest man’s word is as good as his bond] filled me with sincere joy not only in political terms, but also personally.”

Alexander Gorchakov and Otto von Bismarck developed a personal relationship when Russia’s future Chancellor served in Frankfurt am Main as Ambassador to the German Confederation in 1850-1854, and continued when Bismarck was Prussia’s Ambassador to Russia in 1859-1862. This letter refers to a period when Prussia and Russia forged closer ties, with Russia treating the unification of German lands with benevolent neutrality.

|

|

40.

|

.jpg) |

Alexander Gorchakov’s cable message to Russia’s Ambassador to the United States Eduard de Stoeckl on Russia’s decision to sell its American colonies to the United States for $7 million

March 16, 1867

The message instructs the ambassador to hold the talks and sign the treaty.

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

|

|

41.

|

.jpg) |

The US ratification instrument to the Convention between Russia and the United States ceding to the United States of America Russia’s North American colonies of March 18/30 1867

May 28, 1867

Signed by US President Andrew Johnson

Russia sold its American colonies because it found itself unable to retain them any longer considering the lack of proper assets and means in the Pacific Ocean, the threat of a military confrontation with Great Britain, as well as economic factors. The growing amity with the United States was also a factor in countering Britain’s dominance in commerce and navigation. Russia sold its North American colonies for $7.2 million.

|

|

42.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander II’s rescript to Vice-Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov on his appointment as State Chancellor and congratulating him on 50 years of service at the Foreign Ministry

June 13, 1867

“As we mark the 50th anniversary of your public service, it gives me special pleasure to mark this occasion by elevating you to the highest rank in the civil service and appoint you State Chancellor of Foreign Affairs, while cherishing the hope that you will continue guiding the ministry you were entrusted with and contributing to state affairs.”

|

|

43.

|

.jpg) |

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s letter to Emperor Alexander II on his performance as foreign minister in 1856-1867

December 23, 1867

“We must pursue a twofold objective in our political undertakings. First, we must shield Russia from becoming involved in any external complications which could divert it, even if partially, from focusing on promoting development within its borders. Second, we must make every effort to ensure that Europe does not endure any territorial changes, or changes in terms of the balance of power or influence which would be extremely detrimental to Russia’s interests or political stability.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “This is absolutely right and fair. All I can say is that I wish God gives you the strength you need to continue your invaluable service, which no one praises as highly as I do, for a long time to come.”

|

|

44.

|

.jpg) |

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s report to Emperor Alexander II regarding the proposal by the British government to agree on peace terms that would be acceptable for France and Prussia

October 6, 1870

“I believe that we must reject any discussion between neutral countries on the terms for peace, since this matter concerns the warring states only.”

In the 1870-1871 Franco-Prussian War, France opposed a coalition of German states headed by Prussia, who sought to annex Alsace and Lorraine, while also undermining France’s positions in Europe and the colonies. Prussia wanted to build a coalition against France in order to unify German states within a single empire. As for France, it wanted to prevent any territorial losses and the emergence of a unified Germany, as well as overcome the Second Empire’s growing political crisis. The French army’s defeat signalled a radical shift in Europe. Britain and Austria watched eagerly as the conflict unfolded. Alexander Gorchakov considered that this was the best moment for pursuing Russia’s main foreign policy objective to do away with the restrictions set forth by the 1856 Paris Treaty.

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s diplomatic activities in 1870-1878

|

|

45.

|

.jpg) |

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s circular letter to Russian ambassadors to countries that signed the 1856 Paris Treaty

October 19, 1870

The circular letter sets forth the decision by the Russian government to terminate the Black Sea’s neutral status as set forth by the 1856 Paris Treaty. Alexander Gorchakov wrote that while the Russian government complied with the provisions of the 1856 treaty to the letter, other powers violated it on multiple occasions. He went on to note that against this backdrop, Russia no longer considered itself bound by the provisions of the 1856 Paris Treaty limiting its sovereign rights in the Black Sea. He informed the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire about terminating the 1856 Russian-Ottoman convention on the number and sizes of the ships the two coastal nations were allowed to have in the Black Sea. This circular letter was sent to Russian diplomatic representatives in Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy and the Ottoman Empire, and their copies were delivered to the foreign ministers of the corresponding countries. Russia formalised its decision in the 1871 Treaty of London.

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

|

|

46.

|

.jpg) |

Fyodor Tyutchev’s poem “Yes, you have kept your word…” devoted to the termination of Black Sea’s neutral status [1870]

Alexander Gorchakov’s handwriting.

|

|

47.

|

.jpg) |

Treaty between Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France, Great Britain, Italy and the Ottoman Empire revising the resolutions contained in the 1856 Paris Treaty regarding navigation in the Black Sea and along the Danube

March 13, 1871, London

This treaty (convention) resulted from the London conference, which convened in January 1871 in connection with Alexander Gorchakov’s circular letter dated October 19, 1870, terminating the restrictions contained in the 1856 Paris Treaty. It terminated the Black Sea’s neutral status while granting Russia the right to regain its naval presence in the Black Sea and build military fortifications along its coast. This is how Russia restored its sovereign rights on the Black Sea.

|

|

48.

|

.jpg) |

Draft version of a secret political convention between Russia and Austria written by Alexander Gorchakov (autograph)

[May 1873]

Emperors Alexander II of Russia and Franz Joseph I of Austria signed the document in Schönbrunn on May 25/June 6, 1873, to formalise the League of the Three Emperors with the parties undertaking to coordinate their mutual interests when attacked by a third party.

The League of the Three Emperors was an alliance between Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1873-1886. It included several secret political and military treaties.

|

|

49.

|

|

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s cable message to Russia’s Ambassador to France Nikolay Orlov

May 13, 1875

Sent from Berlin, the message reported on a successful effort to resolve a tense situation in Europe caused by the provocative attempt of the German government to start a preventive war against France (the so-called war-scare of 1875): “The Emperor is leaving Berlin confident that peaceful aspirations have prevailed here. The maintenance of peace has been assured.” Alexander Gorchakov wrote this message after the Russian Emperor met with Wilhelm I, who assured the Russian Emperor that Germany did not have any aggressive intentions regarding France. Alexander Gorchakov sent similar messages to the representatives of Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire.

|

|

50.

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s cable message to Russia’s Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Nikolay Ignatyev on the desire to achieve a peaceful resolution of the Eastern question

December 20, 1876

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Then so be it.”

The Eastern question is a term describing a series of international issues in the second half of the 18th century through early 20th century in the context of heightened competition among global powers in the Middle East. Started in the 1850s and until the 1880s, the weakening of the Ottoman Empire brought about a rise in national liberation movements in its territories among the southern Slavs, who benefited from Russia’s support.

|

|

51.

|

.jpg) |

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s letter to Emperor Alexander II on the proceedings of the Congress of Berlin

June 16/28, 1878

In his letter, Alexander Gorchakov writes that the Russian delegation found itself in a challenging situation “when almost all of Europe united its ill-will against us.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note on the document: “Too true!”

|

|

52.

|

.jpg) |

Peace Treaty between Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France, Great Britain, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire for the Settlement of Affairs

July 13, 1878. Berlin

The Treaty of Berlin reversed some of the provisions of the Treaty of San Stefano and formalised Bulgaria’s division into an autonomy with the right to choose its own prince to the north of the Balkan Mountains and the so-called Eastern Rumelia to the south, which remained under the Ottoman Empire, while obtaining some autonomy. New independent countries emerged in the Balkans – Montenegro, Serbia and Romania. The treaty also reaffirmed the status of the Black Sea straits, preventing warships, including the Russian navy, from crossing them without the approval of the Ottoman Empire. The treaty strengthened Britain’s hand and enabled Austria-Hungary to expand its sphere of influence by occupying Bosnia and Herzegovina, while also enabling Germany to improve its image in the Ottoman Empire, as well as around the world. The main provisions contained in the Treaty of Berlin remained in force until the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars.

|

|

53.

|

|

The final meeting of the Congress of Berlin on July 13, 1878

1881

By Anton von Werner

Alexander Gorchakov, seated to the left; Otto von Bismarck as the congress chair shakes the hand of Russia’s Ambassador to Great Britain Pyotr Shuvalov (both standing to the right).

|

|

54.

|

|

Photograph of Alexander Gorchakov

1878

|

|

Reforming the Foreign Ministry. Marking anniversaries of Alexander Gorchakov’s service

|

|

55.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov’s note submitting a draft reform of the Foreign Ministry’s structure for review by the State Council

January 28, 1860

“…I had three undertakings in mind when compiling this draft as set forth by His Majesty the Emperor, specifically, 1) to give more authority to senior executives on the ground, 2) reduce paperwork, and 3) reduce headcount while increasing pay.”

Ever since taking over the Foreign Ministry, Alexander Gorchakov paid special attention to human resources and sought to attract as many competent and talented people as possible to serve there.

|

|

56

|

.jpg) |

Draft Regulations for the Foreign Ministry’s Encryption Service

April 21, 1862

As Vice-Chancellor, Alexander Gorchakov wanted to create a staff-friendly environment for the ministry’s encryption service in order to retain its members. This is why the draft introduced a system of bonuses and offered housing privileges: “Considering that these officials need privacy and isolation from any exposure to external influences, both senior and junior officials working at the Foreign Ministry must be provided with apartments in one of the ministry’s buildings and be housed in a single building.”

Emperor Alexander II’s note: “Then so be it.”

|

|

57.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Ministry circular note to Russia’s diplomatic and consular missions abroad on a fundraiser to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s service

[January 1867]

The note informs its recipients about the decision to present an album with portraits of former and current Foreign Ministry staff members as a gift, as well as “order a big portrait of the Prince to be placed on display forever in the Ministry building.”

“Cognizant as all Russians are of the fact that his lasting service has benefited our Fatherland in such important ways and brought so much prestige to the ministry we belong to, the Foreign Ministry officials wanted to speak their hearts and minds to express in all sincerity what they think about their prominent leader who enjoys universal acclaim and respect.”

|

|

58.

|

|

Portrait of Prince Alexander Gorchakov (ordered by the Foreign Ministry to mark Alexander Gorchakov’s 50 years of service)

1867

By Johann Köler.

|

|

59.

|

.jpg) |

Staffing list of the Foreign Ministry’s headquarters

May 22, 1868

Adopted in 1868, the Foreign Ministry Statute completed the effort initiated by Alexander Gorchakov to reform the ministry’s headquarters. Under the new staffing list, the number of officials decreased from 304 to 134, but the salaries increased, while administrative, archival, maintenance work and translations were outsourced to contractors.

|

|

60.

|

.jpg) |

Draft staffing arrangements for Russian embassies, missions and consulates

December 4, 1874

Russian diplomats and consular workers abroad received their first increase in salary since 1800. This move was designed to improve their wellbeing considering the “growing cost of living” overseas and elevate their living standard to a level that would “match their social status.”

|

|

61.

|

.jpg) |

Foreign Ministry circular note No. 20 about an examination for diplomats entering the ministry, as published by the Foreign Ministry Annuary

October 4, 1875

In 1875, Alexander Gorchakov introduced new recruitment procedures in the Foreign Ministry. Candidates had to go through a selection process, which included writing a memo either in Russian or in French based on a statistical note received in advance. Based on this paper, the examiner interviewed the applicant as part of an oral examination. Aspiring candidates had to know the statistics pertaining to European countries and thus demonstrate their excellence in comparative statistics, as well as the territorial evolution.

Foreign Ministry Annuary. 1877. Pages 109-110.

Launched under Alexander Gorchakov’s ministry in 1861, the Foreign Ministry Annuary published information about the ministry staff based in its headquarters and foreign missions, as well as foreign diplomatic and consular workers, and diplomatic documents.

|

|

62.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander III’s rescript to Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov awarding him a double portrait of the Emperor decorated with diamonds to mark 25 years of Alexander Gorchakov’s appointment as Foreign Minister

April 4, 1881

|

|

63.

|

|

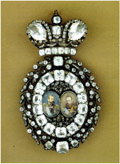

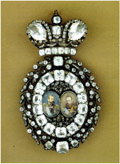

Award pin with portraits of Alexander II and Alexander III

|

|

64.

|

|

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov’s handwritten letter to Deputy Foreign Minister Nikolay Giers thanking him for the initiative to mint a medal celebrating 25 years of Alexander Gorchakov’s work as Foreign Minister

March 24, 1882. Nice

In the letter, Alexander Gorchakov asked that Foreign Ministry staff members Nikolay Giers, Alexander Zhomini and Vladimir Frederiks be awarded medals, as well as to send him ten medals.

Foreign Policy Archive of the Russian Federation, Personnel and Maintenance Department, Series 336/1, File 28, Folder V, Page 262. Original, Russian language

|

|

65.

|

|

Medal In Memory of the 25th Anniversary of Chancellor Prince Alexander Gorchakov Heading the Foreign Ministry. 1856-1881

1881

Designed by Sergey Vazhenin, Mikhel Gabe

|

Family

|

|

66.

|

|

Marriage certificate of Alexander Gorchakov and Maria Musina-Pushkina

August 9, 1838

|

|

67.

|

|

Portrait of Maria Gorchakova

1820s

By Moritz Michael Daffinger

Maria Gorchakova (1801-1853), born Princess Urusova, married General Major Ivan Musin-Pushkin, who died in 1836, leaving her with four sons and a daughter. Maria’s uncle was Dmitry Tatishchev, who served as Russia’s Ambassador to Austria, while Alexander Gorchakov served him there as his Counsellor. Tatishchev opposed his niece’s union with a diplomat devoid of any wealth. Alexander Gorchakov even had to resign and suspend his diplomatic service for a time. The couple had two sons: Mikhail (1839-1897) and Konstantin (1841-1926).

Maria Gorchakova’s beauty made such an impression on Alexander Pushkin that he devoted a poem to her under the title Who Knows the Land Where the Sky Shines…

|

|

68.

|

|

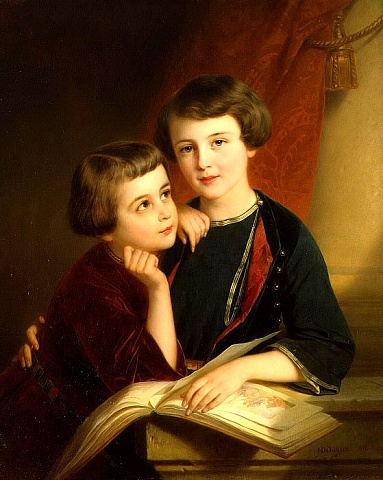

Portrait of Mikhail and Konstantin Gorchakov (from Alexander Gorchakov’s private collection)

1848

By Nicaise de Keyser

Alexander Gorchakov knew the painter well, and after ordering the portrait he allowed it to be displayed during exhibitions in Stuttgart (1848) and Brussels (1851) where it was recognised as one of the best works.

|

|

69.

|

|

Portrait of Konstantin Gorchakov (from Alexander Gorchakov’s private collection)

1868

By Alexandre Cabanel

Born in 1841 in St Petersburg, Konstantin Gorchakov graduated from the St Petersburg University’s Faculty of Law and entered public service in 1863 by joining the Interior Ministry. Having received the rank of a stallmaster in 1872, he went on to become Kiev’s Vice-Governor in 1877-1878. Konstantin Gorchakov was also a businessman and a wine producer. He moved to France after the October Revolution and died in Paris in 1926.

|

|

70.

|

|

Photograph of Mikhail Gorchakov

1878 or later

Born in Moscow on August 24, 1839, Mikhail Gorchakov entered the Foreign Ministry in 1859. He served as Junior Secretary at the Embassy in London since 1862, and went on to become Senior Secretary there in 1864. In 1867, he was appointed Embassy Counsellor in Prussia, and served as Ambassador to Switzerland in 1872-1878, followed by Saxony in 1878-1879. He was Ambassador to Spain in 1879-1896, and died on July 12, 1897.

|

|

71.

|

.jpg) |

Report by Russia’s Ambassador to Switzerland Mikhail Gorchakov to Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov on the congratulations received by incoming President of Switzerland Paul Cérésole on behalf of the diplomatic corps

December 21, 1872/January 2, 1873

In the report, the diplomat discusses his visit to former President of Switzerland Emil Welti to thank him for his cooperation and conveys to the Chancellor New Year greetings on behalf of the Swiss politician.

|

|

72.

|

|

Group photo of Russian diplomats: Mikhail Gorchakov, Andrey Gamburger, Alexander Gorchakov, Arthur von Mohrenheim, Alexander Zhomini

Undated

|

Dismissal. Death. Posterity

|

|

73.

|

.jpg) |

Emperor Alexander III’s rescript to Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov on his dismissal as Foreign Minister while keeping the titles of State Chancellor and Member of the State Council

March 22, 1882

“It is with a profound feeling of sadness that I have come to the conclusion that your health no longer allows you to resume your immediate duties at the helm of the Foreign Ministry. This led me to resolve, following your express desire, to terminate your appointment at the head of this ministry, while preserving your civil service title of State Chancellor, the Empire’s highest civil service rank. In doing so, I am compelled to express my deep gratitude to you for the valorous and glorious accomplishments you achieved while serving the throne and our Fatherland for almost 60 years. Multiple congratulatory rescripts issued by my father, whose memory shall be cherished forever, have celebrated these feats. I hold them in high esteem, and they won you gratitude and respect among our compatriots, inscribing your name in history.”

|

|

74.

|

|

Emperor Alexander III’s cable message to Mikhail Gorchakov in Baden-Baden expressing condolences on Alexander Gorchakov’s passing

February 27, 1883

|

|

75.

|

|

Note by Foreign Ministry Council member Dmitry Stuart to Foreign Minister Nikolay Giers on purchasing a silver wreath for Alexander Gorchakov’s tomb

April 7, 1883

“To Prince Alexander Gorchakov. From the Foreign Ministry and his true admirers.”

|

|

76.

|

|

Monument above Alexander Gorchakov’s tomb

Cemetery of the Coastal Monastery of Saint Sergius (Strelna)

From Alexander Gorchakov's will, dated December 7, 1875: «No matter where I die, it is my wish that my body be put to rest next to my wife, whom I love and mourn so much, in our family plot.”

|

|

78.

|

.jpg) |

Letter by Mikhail and Konstantin Gorchakov to Konstantin Grot, Head of the Office of the Institutions of Empress Maria within His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery, on instituting the Alexander Gorchakov Scholarship at the Alexander Lyceum

July 1883

|

|

79.

|

.jpg) |

Georgy Chicherin, A Historical Account of Alexander Gorchakov’s Diplomatic Service

Early 20th century

Georgy Chicherin wrote this book while serving at the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Empire.

“Prince Gorchakov conducted an honest policy, and even Bismarck recognised this. The Russian government acts honestly and in good faith, Prince Gorchakov used to say. It is for this reason that he preferred to act in a candid manner. Russian politics unfolded “in broad daylight” and “openly,” as he used to say. Gorchakov believed that politics has an honourable mission, which consists of setting reasonable objectives and demonstrating resolve in seeking to achieve them without trying to hide anything under the veil of secrecy. “Only bad players are reluctant to show their hand.” This is why his toolbox included exercising publicity, publishing diplomatic instruments and using the press to influence public opinion.”

|

|

80.

|

|

The Alexander Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Fund is a Russian NGO established in 2010 by the order of the Russian President.

Its mission is to promote public diplomacy and Russia’s foreign policy interests, as well as help create a favourable international social, political and business environment for Russia and engage civil society institutions in foreign policy processes. The fund issues grants to support public diplomacy initiatives.

|

|

81.

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s memorial plaque on the General Staff Building in St Petersburg, where the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Empire had its headquarters in the 19th and early 20th centuries

Architect Tatiana Miloradovich, sculptor Georgy Postnikov

Unveiled in 1998, the plaque was made at the initiative of the Foreign Ministry’s Office in St Petersburg to mark the Chancellor’s 200th birthday.

|

|

82.

|

|

Alexander Gorchakov’s memorial plaque on the building of the Diplomatic Academy

Sculptor Vladimir Surovtsev

Unveiled in 1998, the plaque contains Alexander Gorchakov’s quote: “Russia has a great future, but getting there will not be easy.”

|

|

83.

|

|

Portrait sculpture of Alexander Gorchakov in the Alexander Garden in St Petersburg

Sculptor Albert Charkin

The portrait sculpture was unveiled on October 16, 1998.

|

|

84.

|

|

Memorial plaque on the building where Alexander Gorchakov was born (Haapsalu, Estonia)

Unveiled in 1998, the plaque was updated in 2018. The building currently houses a children’s library.

|

|

85.

|

|

Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov. 200th Birthday, a collection of documents and conference materials

Published in 1998 by Mezhdunarodnye Otnosheniya Publishing House

Edited by Yevgeny Primakov, Igor Ivanov, Yury Ushakov, Pyotr Stegny, Anatoly Torkunov, Andrey Zagorsky.

This volume includes materials from the conference devoted to Alexander Gorchakov’s 200th birthday, held in April 1998, as well as diplomatic documents from the Foreign Policy Archive of the Russian Federation on the Chancellor’s life and career.

|

|

86.

|

|

Overview of the exhibition titled Chancellor Alexander Gorchakov

1998, State Historical Museum

Timed to coincide with Alexander Gorchakov’s 200th birthday, the exhibition was inaugurated by Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov in September 1998. The State Historical Museum, the Foreign Ministry’s Department of History and Records, and the Federal Archive Service of Russia prepared it.

|

|

87.

|

|

Ulitsa Gorchakova metro station in Moscow is located near the street of the same name

It opened on December 27, 2003.

|

|

88.

|

|

Monument to Alexander Gorchakov at MGIMO University

Sculptor Ivan Cherapkin

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov attended the unveiling ceremony to mark the university’s 70th anniversary in 2014. In his remarks, he said that Alexander Gorchakov articulated the basic tenets of Russia’s foreign policy and the country relies on them to this day: “Pursuing our own interests, conducting a multi-pronged foreign policy, including by being ready to engage in dialogue with any country in any region on an equal footing and with mutual respect.”

|

|

89.

|

|

The Gorchakov Lyceum of the MGIMO University

Established on April 8, 2016, at MGIMO University’s Odintsovo branch, this institution is designed to perpetuate the educational traditions of the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum.

|

| 90. |

|

Postage stamp titled History of Russian Diplomacy. 225 Years Since Alexander Gorchakov’s Birth (1798-1883), Chancellor of the Russian Empire.

The stamp is scheduled to be released on June 15, 2023.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)